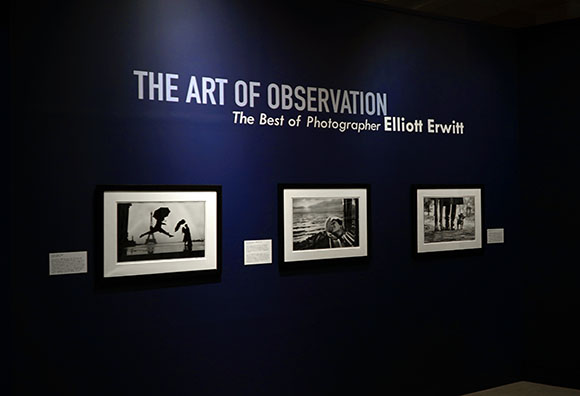

Elliott Erwitt's

Art of Observation

by Steven Hoelscher,

Departments of American Studies and Geography,

Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin © 2015

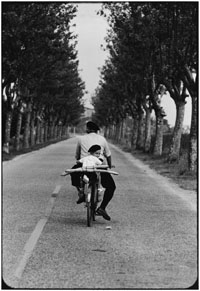

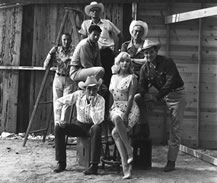

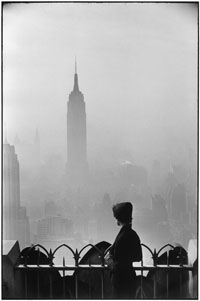

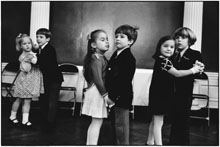

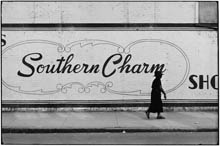

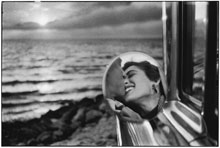

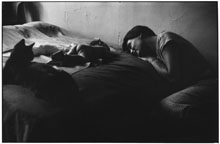

Few photographers have had a greater impact on American visual culture than Elliott Erwitt. Some of his best-known photographs are icons of photo- journalism: Richard Nixon burying his finger in Nikita Krushchev's chest during their so-called Moscow "kitchen debate" in 1959; Jacqueline Kennedy, veiled and in distress at the funeral of her husband in 1963; the unnamed Pittsburgh boy with a pistol to his head. Likewise, his portraits of celebrities like Grace Kelley, Che Guevara, Marilyn Monroe, and Arnold Schwarzenegger have achieved notoriety, but so too have his photographs of everyday life: a couple reflected in the side mirror of a car when they are cuddling; a young mother and her newborn daughter gazing affectionately at each other, much to the approval of a nearby cat. In these and in so many of his photographs, and with a keen visual sense and finely honed wit, Elliott Erwitt illuminates the small moments of life, even when covering major news events. This is how he describes his craft: "To me, photography is an art of observation. It's about finding something interesting in an ordinary place. I've found it has little to do with the thingsyou see and everything to do with the way you see them."

This insightful approach to both photography and the human condition more generally has served Erwitt well. A cosmopolitan by both necessity and profession, Elliott Erwitt has practiced his art of observation across the globe. The only child of displaced Russians, Erwitt was born in Paris, spent the first 11 years of his life in Milan, fled Europe as war approached, and, at 16, found himself living on his own in Los Angeles, where he first developed an interest in photography. But it was in New York that Erwitt met Edward Steichen, Roy Stryker, and Robert Capa, three titans of the photography world who took an interest in the young immigrant and helped launch his career. It was Capa who, in 1953, invited him to join Magnum Photos, the distinguished agency, which elected Erwitt three times to serve as its President. In the 1970s, he expanded his work beyond photography and began making films, both documentary and comedy television. While actively working for magazines, and industrial and advertising clients, Erwitt has created books and exhibitions of his photography. To date, he has published more than 25 photography books including Photographs and Anti-Photographs (1973); Dog Dogs (1998); Museum Watching (1999); Personal Best (2010); Sequentially Yours (2011); Kolor (2013); and most recently Regarding Women (2104). His photographs have been featured in exhibits all around the world including the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Barbican in London, the Kyoto Museum of Contemporary Art, the International Center of Photography, where he was the 2011 recipient of the ICP's Infinity Award for Lifetime Achievement.

The smile that Cartier-Bresson describes stems from Erwitt's life-long project to observe, and then comment on, the human comedy. One of the great masters of humor and irony in photography, Erwitt consistently and poetically captures life's comic parade. For this beloved image- maker, the human comedy is not always funny, but sometimes marked by fear- based hatreds, loneliness, and banality. Elliott Erwitt's art of observation-itself imbued with irony and a tendency toward off-kilter juxtaposition-surveys the human comedy in its endless variety.

What emerges from his camera is a complicated world where the ordinary and absurd reside side-by-side. He may be most well known for his offbeat humor, but that's only part of what makes his photographic art so original. Equally important is a highly developed visual sensibility. This photographer's art of observation reaches its full potential when it captures a memorable moment, or, as Erwitt himself describes it, "a synthesis of a situation, an instant when it all comes together." Regardless of whether the photograph came from his work in photojournalism, as part of an advertising campaign, or as a personal "snap," each memorable picture presents a moment worth pondering. For Erwitt, that moment is decisive if the formal elements of the picture come together to create an original and highly personal comment about the subject. Look at the young boy peering out of the Colorado car in 1955 with the shattered window bullet hole located directly before this right eye. It's a haunting picture and it's up to each of us viewers to decide what that comment is;

Erwitt won't tell us. But that's exactly what makes looking at photographs so rewarding.

- Return to Top - |

.jpg)

2.jpg)